Scientists In Panama Find That Restored Coral Reefs Could Boost Fish Yields By Almost 50%

Image Source: Shaun Low / Unsplash

Scientists at Panama's Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) recently discovered massive potential for overfished coral reefs around the world in a new study aiming to boost sustainability of aquatic environments. After analyzing data using statistical models, researchers approximated current fish populations and predicted potential increases through improved management of overfished coral reefs. With better managements, sustainable fish production could climb by 50%, but wait times for recovery of the coral reefs themselves vary from 6 to 50 years. It may be worth it, as researchers found that annual fish yields could rise by 20,000 to nearly 162 million additional servings from country to country around the world.

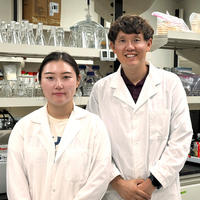

Texas A&M Researchers Develop Probiotic Waste-Based Vegetable Sanitizer

Image Source: Md. Abdur Razzak, Ph.D. / Texas A&M AgriLife

Producing probiotic foods like sauerkraut and kimchi generates thousands of gallons of nutrient-rich liquid that’s typically discarded. Scientists at Texas A&M have discovered a way to up-cycle this fermentation waste liquid into a sustainable food sanitizer. Seockmo Ku, Ph.D., an assistant food science professor, and Min Ji Jang, a doctoral student at the university, recently published their study results in the Chemical Engineering Journal, showing how their up-cycled sanitizer reduced salmonella counts and microbial levels on fresh radish sprouts. Support for the study came from the USDA's National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America, and the World Institute of Kimchi in South Korea.

Canadian Food Scientists Examine Plant-Based Potential In Oil Extrusion Byproducts

Image Source: allybally4b / Pixabay

Demand for plant-based proteins has pushed researchers to look into using oilseed cakes and meals for food products. A group of Canadian researchers from the University of Manitoba recently published a study showing how oilseed-based protein extrusions can be used in food production. The study highlights common plant based protein sources like flaxseeds, peanuts, and soybeans, as well as less explored sources like hemp. The oil-based byproducts of these foods hold valuable nutrients that could be used in cooking oils and plant-based ingredients.

Penn State Researchers Develop Disease-Resistant Cacao Plants With Gene Editing

Image Source: Mark Guiltinan / Penn State

Chocolate prices are rising in part due to crop losses caused by a pathogen called phytophthora. The disease causes cacao yield losses of up to 30% worldwide on a $135 billion-a-year industry. A research team at Penn State University offers hope. The scientists successfully developed a disease-resistant cacao plant using CRISPR-Cas9, a form of gene-editing technology. “We're not just creating better cacao plants, we’re exploring how modern biotechnology can work within existing regulatory frameworks to address real-world agricultural challenges,” said Mark Guiltinan, professor of plant molecular biology in the College of Agricultural Sciences. "Many genetic modification approaches are met with stigma because foreign DNA is left in the final product. Our approach could solve both of those problems,” said Guiltinan.

Scientists Develop Honeybee "Superfood" To Preserve Declining Bee Populations

Image Source: Gwyndaf Hughes / BBC

Honeybees are crucial to the world's agricultural ecosystem and economy. They are responsible for pollinating 70% of global crops, and bee populations have been in rapid decline. In the last decade, annual colony losses have increased by 40 to 50%. Researchers expect this loss rate to accelerate in years to come. To combat the problem, scientists at the University of Oxford, the University of Greenwich, and the Technical University of Denmark have been leading a joint study exploring superfoods for honeybees to preserve healthy colonies. The food includes lipids called sterols, nutrients that bees rely on in the winter and whenever available pollen declines.